High fMET Levels May Make Neutrophils Go Haywire in Vasculitis

Levels of the amino acid rose along with those of inflammation markers in patients

Excess of a particular amino acid, or protein building block, in the blood may make neutrophils — a type of white blood cell that first responds to an infection or injury — more reactive in ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) and large-vessel vasculitis, a study has found.

The amino acid, called N-formyl methionine (fMET), was present at higher levels in the blood of patients with vasculitis than in individuals without the disorder. Researchers also observed that its levels rose along with those of inflammation markers and that fMET might trigger neutrophil activation via its receptor FPR1.

If these findings can be validated in animal studies, they may help set the stage for the development of new treatments for vasculitides. “fMET/FPR1-mediated signaling may be a novel therapeutic target in systemic vasculitides to limit neutrophil-mediated inflammation and tissue damage,” the researchers wrote.

The study, “Neutrophil activation in patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated vasculitis and large-vessel vasculitis,” was published in the journal Arthritis Research & Therapy.

What are neutrophils?

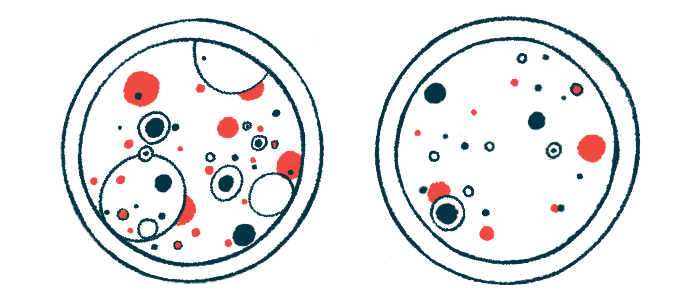

Neutrophils help keep the body healthy by traveling to sites of infection or injury, where they trap bacteria or other foreign particles in lacy structures called NETs, engulf them, and release compounds to destroy them. But when the body makes antibodies targeting its own neutrophils, these white blood cells may go haywire and start attacking cells lining the blood vessels, causing inflammation or vasculitis.

The NETs cast by neutrophils consist of stretches of DNA coiled around proteins. Part of the DNA comes from mitochondria, which burst from the neutrophils. Mitochondria are small structures inside cells that make most of the energy cells need to function properly. They have their own DNA, which is different from the one found in a cell’s nucleus, where genetic information is stored.

Proteins in the body are made from blueprints copied from DNA and their first building block is always the same — even if it gets cut off at a later point in time. For proteins made in mitochondria, as well as in bacteria, that first building block is fMET.

Because fMET is not present in any other proteins of the body, the immune system uses it to tell what is self from what is foreign. Neutrophils can sense proteins starting with fMET, and use them to signal a potential attack.

To find out if fMET plays a role in neutrophil activation in vasculitides, a team in the U.S. measured its levels in the blood of 310 patients and 30 healthy individuals.

The study included 123 patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and 61 patients with microscopic polyangiitis, two types of AAV. There were also 58 patients with Takayasu’s arteritis and 68 patients with giant cell arteritis, two types of vasculitis affecting large blood vessels in the body.

Some blood samples were collected in periods where patients were in remission, meaning they had no symptoms of the disease, while others were collected during a flare, or when the disease was active.

What did the researchers discover?

The researchers found the levels of fMET were higher in the blood of patients than in healthy individuals, regardless of the type of vasculitis. Up to one-third (22%–33%) of patients had “highly elevated levels of fMET.”

They also discovered that fMET levels were correlated with those of C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, two inflammation markers.

In patients with GPA, but not in those with other types of vasculitis, the levels of fMET were higher in those with active disease than in those who were in remission.

In patients in remission, “these [high] levels may indicate subclinical disease activity and smoldering vessel inflammation in systemic vasculitides,” the researchers wrote.

To understand if neutrophils were turned on, the researchers measured the levels of calprotectin, a marker of neutrophil activation. They found the levels were higher in the blood of patients than in healthy individuals, with “neutrophil activation occurring at similar levels in both small and large-vessel vasculitis.”

Moreover, they observed the levels of fMET correlated with those of calprotectin, meaning that patients with high levels of fMET also had high levels of calprotectin.

To confirm the link between fMET and neutrophil activation, the researchers kept neutrophils from healthy individuals in the lab in the absence or presence of a form of fMET. They found the presence of fMET made neutrophils make more of calprotectin, meaning they were more reactive.

In another experiment, the researchers put together neutrophils and plasma, the liquid part of blood, from patients or healthy individuals. Half of the plasma samples from patients — but none of those from healthy individuals — made the neutrophils release reactive oxygen species, which are highly unstable molecules that can cause cell damage.

As a last check to make sure that it was fMET itself that was making neutrophils more reactive, the researchers blocked its receptor, FPR1, using an inhibitor called cyclosporine H. This led to a decrease in the levels of calprotectin and reactive oxygen species.

“Neutrophil activating factors such as fMET peptides are markedly increased in plasma from vasculitis and enhance inflammation through FPR1-mediated neutrophil activation,” the researchers wrote.