Infection risk high for patients on rituximab with low antibody levels

Patients who received pneumococcal vaccine had lower risk in real-life study

Written by |

People with ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) who develop low antibody levels associated with rituximab treatment are at high risk of serious infections, a new study from France highlights.

“Our real-life study provides useful information to answer a practical question: what is the risk of [serious infection] when initiating or continuing rituximab therapy in” a patient with low antibody levels, the researchers wrote.

Findings also showed that patients who received a pneumococcal vaccine — which protects against certain types of bacterial infections — were at lower risk of serious infections. This supports the importance of getting recommended vaccinations before starting on this immunosuppressive therapy.

The study, “Infectious risk when prescribing rituximab in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia acquired in the setting of autoimmune diseases,” was published in International Immunopharmacology.

Rituximab — sold under the brand name Rituxan, with biosimilars also available — is an infusion therapy that works to deplete immune B-cells, which are responsible for producing antibodies, including the self-targeting antibodies that drive AAV.

Low antibody levels common with rituximab

Rituximab has been widely used in the management of AAV and other autoimmune diseases where B-cells play a central role.

But because antibodies also play key roles in defending the body against infection, the B-cell-depleting effects of rituximab can commonly cause low antibody levels — known as hypogammaglobulinemia — and increase infection risk.

Due to the risk of infection associated with immunosuppressive therapies like rituximab, it’s broadly recommended patients receive all recommended vaccinations before starting on such medications. The pneumococcal vaccine that protects against any type of infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria is usually recommended.

Now, researchers evaluated rates of serious infections for 121 adults with autoimmune conditions, including 48 AAV patients, who received at least one additional rituximab infusion following the detection of hypogammaglobulinemia as a side effect of rituximab.

All patients were treated at the University Hospital of Toulouse, in France, between January 2010 and December 2018. Besides AAV patients, 48 people had multiple sclerosis (MS) or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) — autoimmune diseases that impact the brain and spinal cord — and 25 had other autoimmune diseases.

Most of the patients were followed for two years after hypogammaglobulinemia detection. Over this time, serious infections were reported in 26 of the patients (21.5%), with most of them (57.7%) affecting the lungs.

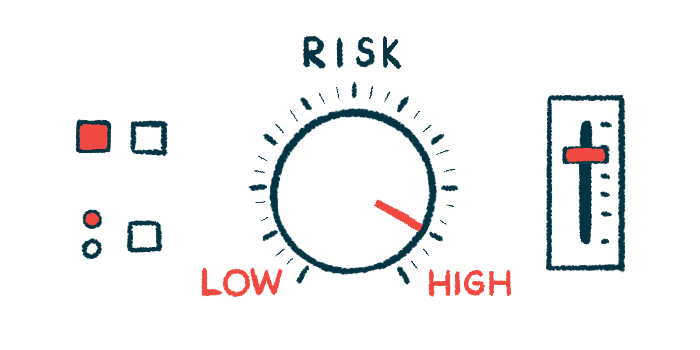

Patients with moderate hypogammaglobulinemia were more likely to have a serious infection than those with mild hypogammaglobulinemia (46% vs. 20.2%).

The two-year cumulative frequency rate of serious infections was 27.6% in the AAV group. This rate was notably lower (12.7%) for patients with MS or NMOSD and slightly higher (30.6%) for the group of patients with other autoimmune diseases.

The scientists then conducted statistical analyses to identify risk factors of serious infections. Results showed that the risk of infection was more than three times higher among patients with lung disease and among those who had not received a pneumococcal vaccine.

“Pneumococcal vaccination was clearly associated with a lower risk of infection, and especially lung infection, in our study, which has been reported previously,” the researchers wrote. “These results are additional arguments to encourage vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae in these patients.”

Infection risk also was significantly increased by about fourfold among patients who were receiving corticosteroids along with rituximab and by more than 2.5 times among those who had previously been treated with cyclophosphamide.

Also, low counts of lymphocytes (a class of immune cells that includes both B-cells and T-cells) and more severe co-occurring health conditions each were each associated with a twice as high risk of serious infection. These findings are broadly in line with prior research, the researchers noted.

While men were found to have a nearly 2.5 times higher risk of serious infection, this association failed to reach statistical significance, meaning it may be due to random chance.

The researchers highlighted their study was limited by the small number of included patients from a single center and its retrospective nature, so further studies will be needed to verify and expand on these results.

“These results must be confirmed in a multicentric prospective independent [group of patients] of expertise center and [appropriately-controlled] trials,” they wrote.