CD64 Levels in Neutrophils Distinguish Infection From Active Disease in AAV, Lupus, Study Reports

Written by |

Elevated levels of the CD64 protein on the surface of neutrophils – a type of immune cell – accurately distinguishes bacterial infection from disease flares in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a study has found.

The study, “Utility of neutrophil CD64 and serum TREM-1 in distinguishing bacterial infection from disease flare in SLE and ANCA-associated vasculitis,” was published in the journal Clinical Rheumatology.

Patients with autoimmune diseases such as AAV and SLE usually receive several immunosuppressive medications to keep their disease in check. These agents dampen the immune system, making patients more prone to developing infections — a major cause of death in these populations.

While it is critical that physicians accurately identify patients with infections, symptoms of these conditions — fever, joint pain, and shortness of breath — are often nonspecific and overlap with common signs of infection.

“The complexity of the clinical presentation of both infections and active disease creates the need of biomarker that can reliably differentiate between the two,” the researchers wrote.

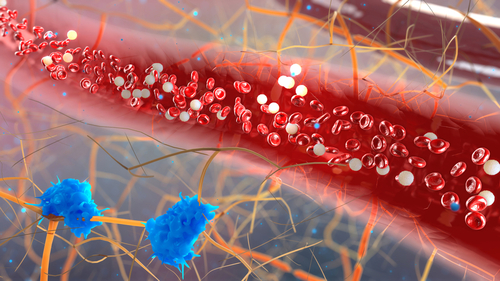

Recently, the levels of a receptor protein, called CD64, located on the surface of neutrophils, has been shown to increase rapidly in response to an infection.

Another receptor protein, called TREM-1, located on the surface of myeloid cells, was first identified as a crucial mediator of septic shock. TREM-1 levels in circulation — soluble TREM-1 — have also been suggested as a potential marker of bacterial infection.

Researchers have now evaluated the clinical potential of CD64 in neutrophils and soluble TREM-1 to differentiate between systemic infection and active disease in patients with AAV and SLE.

The study included 76 patients — including 51 with active disease (16 AAV and 25 SLE) and 25 with a bacterial infection (21 SLE and 4 AAV) — and 20 healthy individuals used as controls.

Most patients with infections (72%) and active disease (73%) had a fever. The most common bacteria found in the infected patients included Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, Pneumococcus, and Pseudomonas.

Researchers measured CD64 in blood neutrophils, soluble TREM-1, and procalcitonin, an established marker of systemic bacterial infections.

The percentage of neutrophils producing the CD64 factor was significantly higher in patients with an infection (69%) than in patients with active disease (7.7%) and healthy controls (7.1%).

Using a cut-off value of 30%, the levels of CD64 had a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 84% in differentiating disease activity from bacterial infection. This means that among patients with more than 30% of neutrophils producing the CD64 protein, 85% actually had an infection. Only 16% were false positives for infection.

The accuracy of procalcitonin was lower, with a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 85%. And while combining both factors reduced the false positive rate to 3%, it increased the number of false negatives to 36%.

While the levels of soluble TREM-1 were higher in patients with disease activity and infection than in controls, the researchers found no significant differences between patients with disease activity and infection.

Other lab parameters, such as total white cell count or the levels of anti-myeloperoxidase and anti-proteinase-3 levels — two types of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCAs) — were not significantly different in patients with active disease and infection.

“We propose that nCD64 [neutrophil CD64] expression may be a useful tool in those patients with SLE and AAV who present with non-specific symptoms such as fever, suggesting either flare of the underlying disease or systemic infection,” the researchers wrote.

“The role of sTREM-1 needs to be studied further to see if it can be used as a biomarker of infection in patients with SLE and AAV, although in our study, it was not found to be useful,” they added.