Reduced dose of cancer drug helps AAV patients, study finds

Single-center study shows obinutuzumab is 'promising therapeutic alternative'

Written by |

A reduced dose of obinutuzumab, an immunosuppressant approved for certain blood cancers, safely helped most adults with ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) achieve sustained disease remission, while reducing their need for standard glucocorticoids.

That’s according to a single-center study in China involving 12 adults with hard-to-treat AAV and four adults with severe disease who had not received prior treatment. Data showed that the treatment was generally safe and associated with reduced disease markers and improved kidney and lung function, with benefits lasting up to 1.5 years.

These findings establish obinutuzumab as “a promising therapeutic alternative,” particularly for patients in whom standard therapies have failed, the researchers wrote. They emphasized, however, that larger studies are needed to confirm the results and determine optimal dosing.

The study, “Reduced-dose obinutuzumab induces remission in refractory ANCA-associated vasculitis: a report of 16 cases,” was published in Frontiers in Immunology.

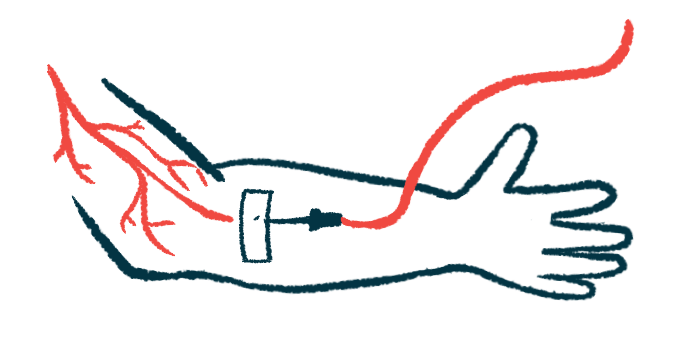

AAV is a group of autoimmune diseases in which self-reactive antibodies, called ANCAs, drive inflammation and damage to small blood vessels. Depending on which blood vessels are affected, different organs can be involved — most often the kidneys and lungs — leading to a wide range of AAV symptoms.

Options few for those who don’t respond to standard treatments

Standard AAV treatment typically combines glucocorticoids, such as prednisone, to quickly control inflammation, with immunosuppressive medications like cyclophosphamide or rituximab.

Cyclophosphamide, sold as Cytoxan with generics available, has long been prescribed off-label for AAV. Originally developed as a cancer treatment, it works by killing overactive immune cells.

Rituximab is an antibody-based therapy approved in the U.S. and other regions for granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), the two most common types of AAV.

Marketed as Rituxan and MabThera, with biosimilars available, it targets CD20, a protein found on the surface of antibody-producing immune B-cells, promoting their death.

“However, there is no universally accepted alternative treatment for patients who fail or are intolerant to [rituximab/cyclophosphamide], highlighting the need for additional options,” the researchers wrote.

Obinutuzumab is a next-generation, anti-CD20 antibody-based therapy approved for certain blood cancers under the brand names Gazyva and Gazyvaro. It is engineered to achieve deeper and longer-lasting B-cell depletion than rituximab.

The therapy has also shown efficacy signs in autoimmune diseases, such as lupus. Yet, “robust evidence for obinutuzumab in AAV is limited,” the researchers wrote.

The team retrospectively analyzed data from 16 adults with active MPA or GPA who were treated with obinutuzumab at Shanghai Renji Hospital in China.

Participants had a median age of 44.5, and nearly two-thirds (62.5%) were men. A total of 12 people (75%) had relapsing disease, with all but one failing to respond to cyclophosphamide and/or rituximab. The remaining four people (25%) had newly diagnosed severe AAV and had not received previous treatment.

ANCAs were detected in the blood of all participants. The mean Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS), a standard measure of AAV activity, was 13.5, indicating active disease, and most were on high doses of prednisone (up to 60 mg/day).

The most commonly affected organs were the lungs (63%) and kidneys (38%), followed by the eyes (31%) and ear, nose, and throat (25%).

Participants received a single into-the-vein infusion of 1,000 mg obinutuzumab as an exploratory low induction dose. Some also received maintenance therapy with either obinutuzumab or rituximab. All patients were followed for 76 weeks, or nearly 1.5 years.

Results showed that all participants responded to obinutuzumab, as defined by a more than 50% reduction on the BVAS without new disease manifestations.

After about six months, half had achieved complete remission, defined as a BVAS of zero and an oral prednisone dose of 10 mg/day or less. This was met by 41.7% of those with relapsing disease and 75% of newly diagnosed patients. Nearly 70% of participants had a BVAS of 0, indicating no active disease.

By the end of follow-up, 81.3% of all patients were in remission. All were able to taper prednisone to 5 mg/day or less, and one discontinued glucocorticoids altogether. A single AAV relapse occurred during the study.

Laboratory findings mirrored these clinical improvements. By 24 weeks, ANCAs were no longer detectable in all patients, B-cell counts fell to zero, and markers of inflammation dropped significantly. Kidney and lung function also improved.

“Rapid clinical improvement was evident within the first 4 weeks of obinutuzumab and persisted for approximately 52 weeks [about a year],” the team wrote, after which B-cell counts and ANCA levels began to rise again. Still, kidney function appeared to remain stable through 1.5 years.

The therapy was generally well tolerated. Infections occurred in 43.8% of participants, mostly affecting the respiratory tract. Three infusion-related reactions were reported, all resolving after a brief adjustment of the infusion rate.

“This study offers critical real-world evidence supporting obinutuzumab as an experimental treatment option for AAV, leveraging its potent B-cell-depleting activity,” the team wrote. “Future investigations should prioritize dose optimization strategies, rigorous immune function surveillance, and extended follow-up to definitively establish the therapeutic role of obinutuzumab in AAV.”