Study Links White Blood Cell Precursors to Vasculitis Severity at Diagnosis

The more white blood cell precursors that an ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) patient has when diagnosed, the worse their disease, a South Korean study reports.

Levels of the precursors, known as immature granulocytes, can help doctors identify which patients with two forms of AAV are likely to have relapses, the researchers said. Those forms are granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

The study, “Delta Neutrophil Index Is Associated with Vasculitis Activity and Risk of Relapse in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis,” appeared in the Yonsei Medical Journal.

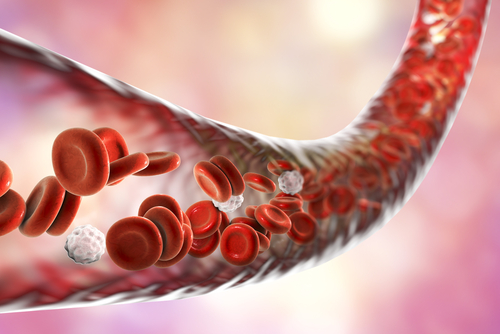

ANCA antibodies activate an immune cell called a neutrophil in ANCA vasculitis patients. The cells migrate to tissue adjacent to blood vessels, inflaming the vessels — the hallmark of the disease.

As neutrophils leave the bloodstream, the number of immature granulocytes rises. These are the cells that differentiate into neutrophils.

Scientists have identified the level of immature granulocutes in the blood as a potential marker of inflammation and infectious diseases. But until the Korean study, little had been known about its role in ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Researchers at Yonsei University College of Medicine wanted to learn more. They looked at the records of 97 people with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Among them, 20 had GPA, 58 had MPA, and 19 had eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).

Seventy patients had anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies (MPO-ANCA) and 15 had proteinase 3 antibodies (PR3-ANCA). A measure called the Delta Neutrophil Index (DNI) is used to measure the levels of immature granulocutes in patients’ blood stream — and the study participants’ DNI scores averaged 1.5% when they were diagnosed. In addition, 29% of patients had relapses after their diagnosis.

Researchers found a significant correlation between DNI and disease activity, with the measure they used being the Birmingham vasculitis activity score (BVAS).

But an analysis by AAV subtype showed that DNI was associated only with GPA and MPA severity at diagnosis, but not with EGPA activity.

DNI was also significantly correlated with some biochemical parameters, including white blood cell counts, fasting glucose levels, and amount of C-reactive protein — a marker of inflammation.

Those with a DNI of 0.65% or higher at diagnosis were 4.26 times more likely to have severe vasculitis, the researchers found.

The team also looked at whether DNI could predict relapse in GPA and MPA patients. They discovered that a DNI of 0.65% or higher at diagnosis was associated with lower relapse-free rates after 50 months than a DNI lower than 0.65%.

Collectively, the findings suggested that DNI can help doctors determine MPA and GPA severity at diagnosis and predict relapses.

Because the study was based on a medical record analysis, the researchers were not able to determine an association between DNI values and disease activity scores over time. They called for additional studies with more patients and a more dynamic monitoring approach to further investigate DNI’s role in vasculitis.

Nonetheless, the team suggested that “patients having high DNI at diagnosis should receive more immediate and aggressive treatment.” This approach could reduce relapses and increase the chance of tissue recovery, they added.